We set the stage by looking at the events leading up to Christmas Day, 1869. We’ll shine a light on the key players who become the important figures in the story. (60m)

After Christmas Day 1869 turned into a bloody mess, the United States Army opened fire on the Tlingit village of Ḵaachx̱ an.áakʼw. The bombardment lasted two days, and ended with the first murder trial held by the United States in Alaska. (60m)

The Bombardment of Wrangell

Experts Speak

Dr. Rosita Worl of Sealaska Heritage Institute speaks on the legacy of bombardments in Alaska.

Anthropologist Dr. Zachary Jones, author of the 2015 National Park Service report on the bombardment, speaks on the impact of Alaska’s bombardments.

Ronan Rooney of Wrangell History Unlocked presents a timeline of the Bombardment of Wrangell at the Sharing Our Knowledge Conference in 2022.

U.S. Government Sources

December 1869 Fort Wrangel Army Post Returns

The U.S. Army’s hand-written Post Return for Fort Wrangel in December 1869 contains a brief summary of the events surrounding the bombardment.

March 1870 Citizens Imprisoned or Detained in Military Custody

This report by President U.S. Grant identifies the two scapegoats for the bombardment, John Cassin and James Holleywood.

Contains the officers’ written reports, Indian Commissioner Vincent Colyer’s scathing takedown, and written testimonials gathered by Colyer.

Newspaper Sources

January 18, 1870 British Daily Colonist

The British Daily Colonist published one of the first accounts of the bombardment based on its own reporting.

January 25, 1870 Daily Alta California

California’s Daily Alta newspaper published an original account of the bombardment.

January 26, 1870 San Francisco Chronicle

The San Francisco Chronicle published an original account of the bombardment. (Note: link requires newspapers.com membership)

February 7, 1870 Philadelphia Inquirer (SF Bulletin Reprint)

The Philadelphia Inquirer reprinted an article originally featured in the San Francisco Bulletin. (Note: link requires newspapers.com membership)

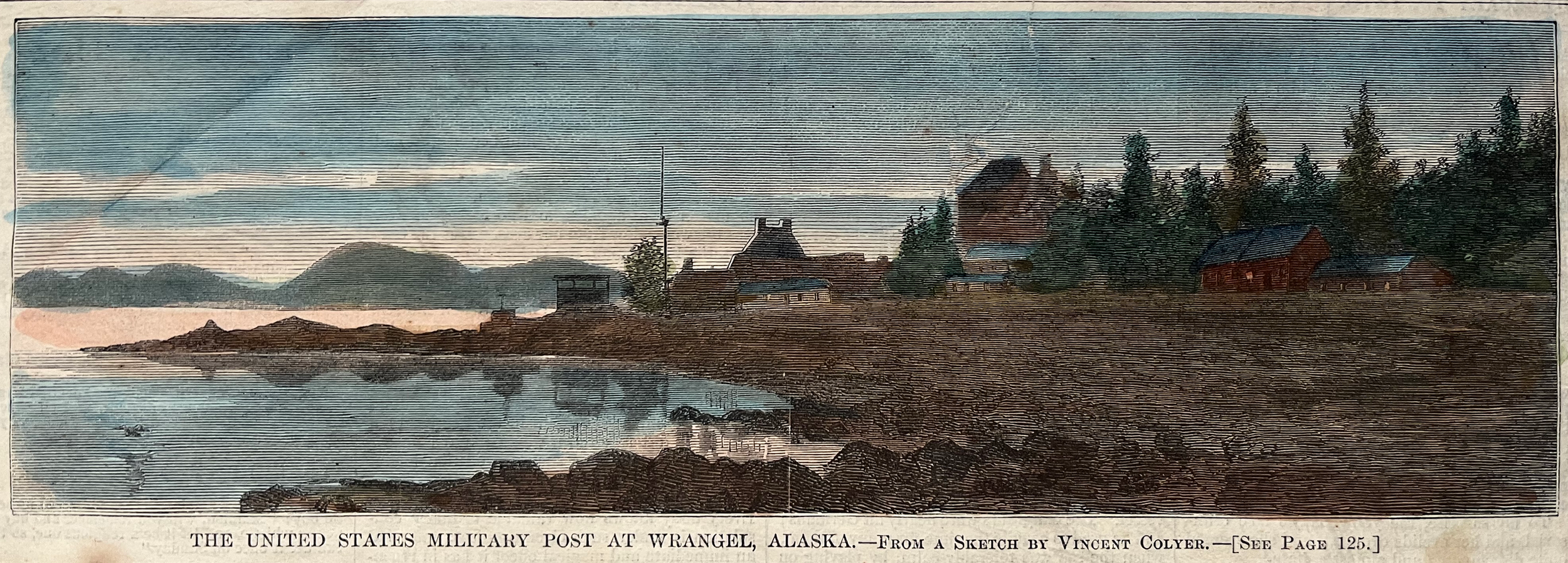

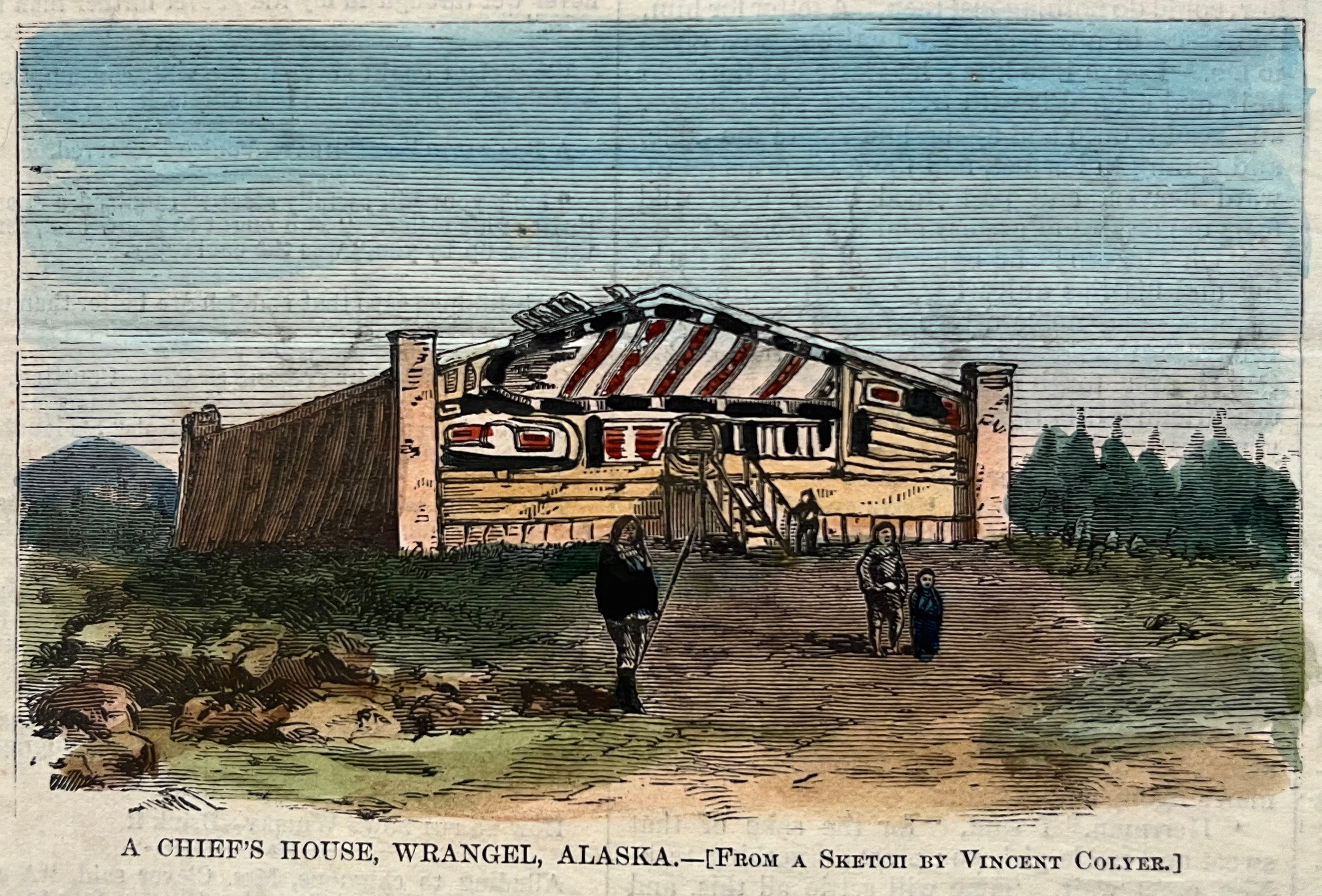

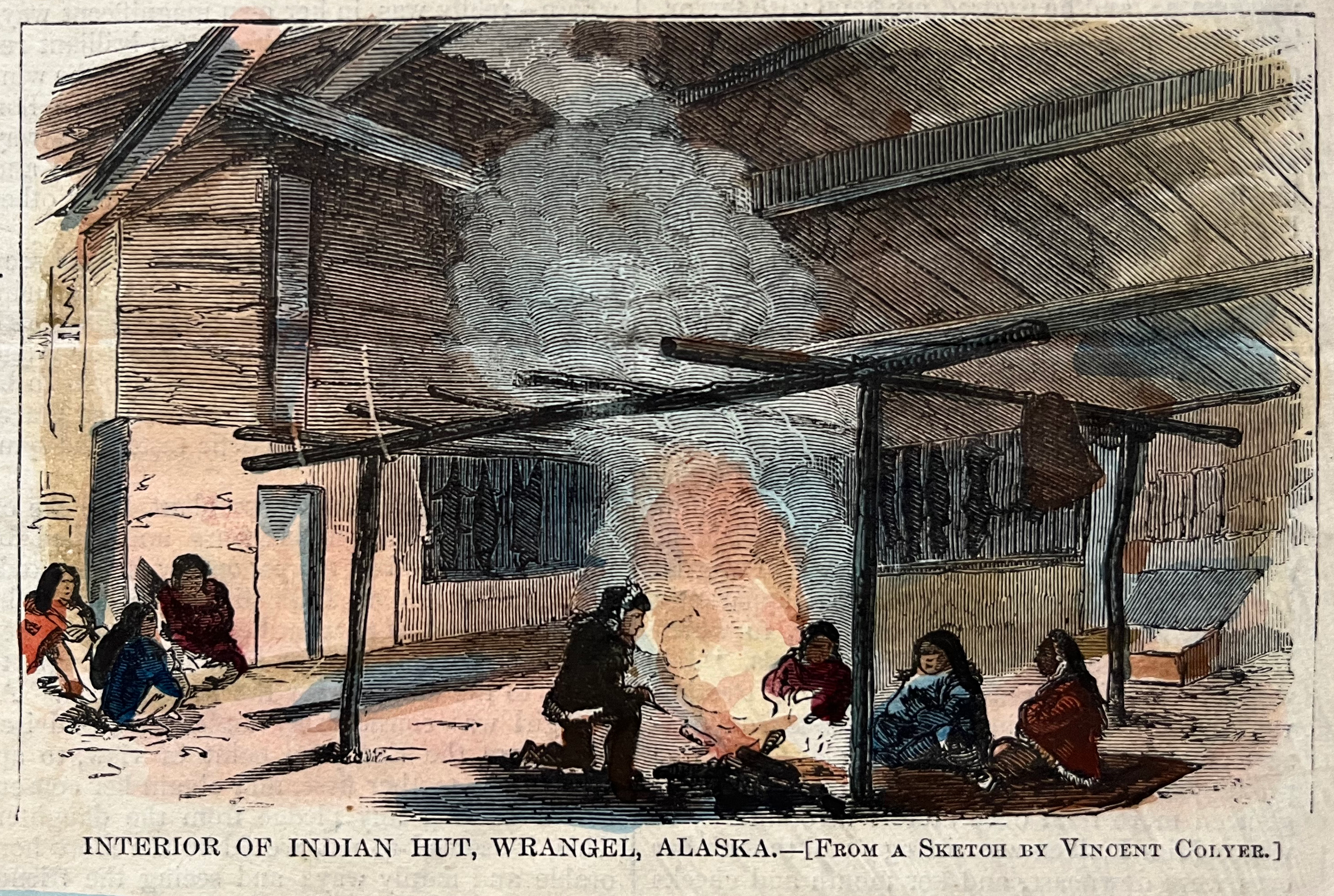

February 19, 1870 Harper’s Weekly

Harper’s Weekly was a widely-circulated magazine, and its devotion of a full page spread to Vincent Colyer’s illustrations helped to raise awareness of the bombardment to the public.

Tlingit Sources

June 1940 William Tamaree in the Wrangell Sentinel

The Wrangell Sentinel interviewed Tlingit elder William Tamaree about his recollections of the bombardment when he was a young boy.

1953 William Tamaree Tape Cassette Recording

While the original tape recording is only available through Sealaska Heritage Institute, a transcript is in the 2015 bombardment report.

1969 Thomas Ukas in “Notes from the Century Before”

In the 1960s, Edward Hoagland traveled up the coast of British Columbia and southeast Alaska and gathered stories from locals, including a bombardment story by Tlingit elder Thomas Ukas.

Blog Posts

“Repugnance and Reluctance:” The Personnel Files of Lt. Melville Loucks

Lt. Melville Loucks played a critical role in the days of the bombardment, but military leaders considered him a poor officer.

Walking the Bombardment of Wrangell

While Wrangell has grown since 1869, many of the places mentioned in the Bombardment of Wrangell story can still be visited on foot today.

The Man Who Bombed Ḵaachx̱ana.áakʼw

Lt. William Borrowe oversaw the bombardment on December 26, 1869, but his personnel file reveals a career of lies, scheming, and deceit.

Etched in Memory: The Artwork of Vincent Colyer

Prior to the bombardment, Vincent Colyer visited Ḵaachx̱ana.áakʼw on behalf of the government and painted landscape images of the village.

Historical Timeline

October 1867 - U.S. Army In Alaska

October 18, 1867: Russia formally transfers its holdings in Alaska to the United States at a ceremony in Sitka. Russia’s footprint in Alaska is relatively small. It includes a military headquarters in Sitka and a long-abandoned, dilapidated post in what is today Wrangell.

Spring 1868: The Army sends a detachment of soldiers from Sitka to establish Fort Wrangel. Soldiers sleep in tents as workers, including hired local Tlingit laborers, clear the land of stumps and begin construction of a large fence and buildings.

September 1868: William King Lear, an Army veteran and former merchant of the Frasier River Gold Rush, arrives in Fort Wrangel to open a trading post. As a post-sutler, Lear’s job is to sell goods to the soldiers and families stationed at Fort Wrangel. (For a complete history, check out our podcast episode, King Lear of Wrangell.)

October 1868: William Borrowe is sent to Fort Wrangel, where he reports to Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Grey.

1869: Lieutenant Melville Loucks became Fort Wrangel’s second-in-command, reporting only to William Borrowe. (Read our blog post about the personnel files of Melville Loucks). Shortly before coming to Alaska, Melville Loucks graduated near the bottom of his class at West Point. While serving at Fort Wrangel, he acquired a Tlingit Pipe and Tlingit Rattle onto which he carved: “Made By the Alasky Indians — Brought by MR Loucks First Lieutenant Officer.”

February 1869: In an event dubbed The Bombardment of Kake, the USS Saginaw destroys the village of Kake, sending its Tlingit villagers into the wilderness during the cold winter season.

March 1869: Former Confederate navy Captain Leon Smith arrives at Fort Wrangel with his wife and young son. Smith enters into business with William King Lear. Together, they run a trading post and a bowling alley down the hill from the newly constructed Fort Wrangel. Of the Tlingit, Smith reports:

“I have found them to be quiet, and seem well disposed toward the whites… They take up salmon, fish oil, blankets, domestics, red cloth, beads, molasses, flour, and in fact every other article suitable for Indian trade… The Stick tribe is a very honest tribe, and partial to the whites.”

Ocobter 1869 - Vincent Colyer In Fort Wrangel

October 1869. Humanitarian-worker Vincent Colyer is sent to Fort Wrangel to assess the conditions. Colyer is famous for his work among marginalized people. President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Colyer to the newly formed Board of Indian Commissioners in order to advise the government on Indian policy. Wherever he went, Vincent Colyer created illustrations of the people and places he visited. In Alaska, he creates detailed illustrations of life in Fort Wrangel and Ḵaachx̱ an.áakʼw. (Read more on the blog, Etched in Memory: The Artwork of Vincent Colyer).

Vincent Colyer personally visits 32 homes in kaach.xan.a’kw to perform a village census. He counts a total of 508 people. Every home contains at least one child. Most of the village (54%) are female.

December 25, 1869 - Christmas Party

Christmas Morning: At the invitation of Fort Wrangel’s commander, Lieutenant William Borrowe, Tlingit men and women come to the fort for a day-long party. Neither of the lieutenants in command of Fort Wrangel would later admit to this party in their written reports, but multiple newspaper accounts and William Tamaree describe the party in detail.

“Early on the morning of Christmas Day the Indians, all prepared for merry-making, left their settlements and repaired in swarms to the garrison. Here the soldiers had made ample preparations for their entertainment, and the whole day was a continued round of pleasure and festivities… Liquors were freely circulated.”

Christmas Evening: The sun begins dimming around 4:03pm, becoming fully dark by 5:39pm. Despite Army regulations banning Indians inside the fort after sunset, the party continues inside the fort’s largest building, the two-story Hospital building.

Christmas Late Night: Among the soldiers at Fort Wrangel are an accordion player and a violin player, who create music for dancing. A Tlingit woman, Kchok-een, is humiliated when the Army men laugh at her for falling on the dancefloor. In response, her husband, Shawaan, pushes her down the stairs. At the foot of the stairs, Angelina Muller, the wife of the fort’s quartermaster, recovers Kchok-een and attempts to protect her from Shawaan in an anteroom. Shawaan struggles against Angelina Muller to push open the door, and in the process bites off her finger.

According to William Tamaree, Shawaan is shot dead almost immediately and Shawaan’s brother, Isteen, is mortally wounded. According to written reports of Lieutenants Borrowe and Loucks, the brothers were shot inside a home in the village of Kaach.xan.a’kw in a failed attempted arrest.

December 26, 1869 - Bombardment Day 1

December 26 Before Sunrise: Both Tamaree and the Army reports agree that the Army sent a detachment of soldiers into the village in the middle of the night, early on December 26. Tamaree describes Lieutenant Loucks as threatening and challenging the Tlingit to fight.

Meanwhile, Shawaan and Isteen’s father, Scutdoo, is awoken from his sleep by his wife, who reports the the shootings. In the reciprocal-based system of Tlingit justice, Scutdoo feels compelled to atone for Shawaan’s death at the hands of the White men by shooting a White man, to even the balance. Scutdoo takes a rifle with him, and on a chance encounter, shoots merchant Leon Smith outside of his store. Read here to learn about the spot where Scutdoo (Shx’atoo) shoots Smith. Scutdoo flees into the woods.

From inside the fort, Lieutenant Melville Loucks hears Scutdoo’s rifle discharge and runs to find Leon Smith struck and bleeding on the ground. Loucks and fellow soldiers take Smith into the fort.

An unidentified Tlingit woman visits the fort in the dark morning hours to consult with commander Lieutenant William Borrowe. He tells her to tell the chiefs of the tribe that unless Scutdoo is turned over, the Army will bombard the village.

December 26 After Sunrise: Lieutenant Melville Loucks returns to the village with 20 enlisted men to deliver Borrowe’s ultimatum: turn over Scutdoo, or the villagers will be bombarded and hunted down. The villagers reply they don’t know where Scutdoo is. Loucks returns to the fort without any concessions. Loucks relies on a translator named William Wall who may have been speaking “Chinook Jargon.”

December 26 Late Morning: Lieutenant Borrowe relies on a man named Kaacheinee to deliver his message to the village leaders. Kaacheinee walks from the fort to Shakes Island and back three times to deliver messages.

December 26, 2pm: The Army begins shooting cannons at Kaach.xan.a’kw. While some Tlingit people flee into the areas south of the village beyond the range of the cannons, others take up arms and assault the Army fort from the high vantage ground of what is today called Mt. Dewey. The Army responds by firing scatter shot from their cannons.

December 26, Sunset: After a long afternoon of steady cannon fire, the Army ceases fire for the day.

December 26, After Sunset: According to Tamaree, Shakes and Towatt visit the fort for a private discussion with Lieutenant William Borrowe, where Shakes agrees to turn over Scutdoo, if the Army will turn over the man who killed Shawaan. Borrowe reportedly says he will consider it.

December 27, 1869 - Bombardment Day 2

December 27, Sunrise: Shortly after sunrise, the Army reports gunfire attacking the fort from the direction of the village. After several rounds of exploding shells hit Shakes Island, the Tlingit approach seeking terms of surrender. Lieutenant Borrowe describes taking Scutdoo’s mother and another man as hostage, pending the return of Scutdoo.

December 27, Mid-Day: Scutdoo emerges from hiding in the woods to walk through the village one last time. He makes his way around Etolin Harbor, ending at the home of Shustack near the end of the peninsula in front of the town.

December 27, Evening: Scutdoo is taken across the water, from Shustack’s Point to the fort, where he surrenders to the U.S. Army. Lieutenant William Borrowe orders Scutdoo placed in the guardhouse. No more shots will be fired in the conflict.

In the whole bombardment, the Army fired 15 rounds of solid shot cannonballs, 4 canisters of scatter shot, 4 exploding shells, and 110 rounds of ball cartridge.

December 28, 1869 - Court-Martial

December 28, 1969: Even though Scutdoo is a civilian, Lieutenant William Borrowe orders a court-martial trial for him. The judges and jury of the court-martial include Borrowe, Lieutenant Melville Loucks, Dr. Henry Kirke, and the late Leon Smith’s business partner, William King Lear. The court-martial finds Scutdoo guilty of murder and orders him hanged the next day.

December 29, 1869 - Execution Day

December 29, 1869: Scutdoo is hanged in full view of his fellow villagers. Scutdoo is the first of twelve executions carried out in Alaska under the United States. Nine years later, Alaska’s second execution also takes place in Fort Wrangel. (For a complete history, check out our episode The Trial of John Boyd for the Murder of Thomas O’Brien).

According to AlternateWars.net, the U.S. Army spent most of 1869 engaged in conflicts with Indigenous people. Red X’s on this calendar indicate a date of conflict.

1870 - Backlash

January 1870: Newspapers along the west coast report on the bombardment. Many of them crib details from the officers’ written reports, but they also include additional details omitted by the officers, such as the drunken party on the day of Christmas 1869.

February 19, 1870: Harper’s Magazine runs full-page reproductions of Vincent Colyer’s illustrations, along with his quote:

“The villagers, Mr. Colyer thinks, will now be afraid to occupy their houses again for the winter, and will be greater sufferers by this act of the commandant. The inhabitants were quiet, honest, and well-disposed toward the whites, and it is very much to be regretted that the commandant of the post should not have been more judicious in his treatment of them.”

March 1870: The U.S. Senate formally requests the Secretary of War to investigate and explain the event being called “The Bombardment of Wrangel.”

April 1870: In response to the Senate’s request, Vincent Colyer publishes a report on the bombardment dubbed The Colyer Report. He writes:

“The military reports show that this bombardment was the result of a wanton and unjustifiable killing of an Indian named Shawaan by Lieutenant Loucks, the second officer in command of the post... Nowhere else that I have visited is the absolute uselessness of soldiers so apparent as in Alaska… The soldiers will have whisky, and the Indians are equally fond of it. The free use of this by both soldiers and Indians, together with the other debaucheries between them, rapidly demoralize both.”

January 1871: Lieutenant William Borrowe is forced out of the U.S. Army, this time for good.

1962: The U.S. Army publishes Building Alaska with the US Army:

“The post commander regretted the extreme measures, but under the circumstances nothing else would have brought Scutdoo to justice.”

1990: Former Wrangell Sentinel editor Jamie Bryson publishes The War Canoe, a novel set in Wrangell that heavily features the bombardment in its storyline. The appendix includes a complete copy of The Colyer Report.

2015: Anthropologist Dr. Zachary Jones publishes The 1869 Bombardment of Ḵaachx̱an.áakʼw from Fort Wrangell: The U.S. Army Response to Tlingit Law, Wrangell, Alaska. The paper includes Tlingit translations by David Katzeek and Ishmael Hope. The paper is published under a grant from the National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program, along with collaboration from the Wrangell Cooperative Association, the City and Borough of Wrangell, and Sealaska Heritage Institute.

Listen to the Episode:

NEXT IN THE TIMELINE:

If you are interested in what happens in Wrangell history after the bombardment, check out Strange Customs: The Corrupt Collector John Carr. This 3-part series covers the years after the bombardment, when Fort Wrangel goes from an abandoned Army post to hotbed of activity with the Cassiar Gold Rush.